Vet's Corner

- Vet's Corner

- Disease Syndromes

- Abortion in Angora goats

- Birth abnormalities in Angora kids

- BLINDNESS or ‘Apparent Blindness’ in Angora Goats

- Diarrhoea in Angora Goats

- Tulp - Morea spp

- EYE - BLUE DISCOLOURATION

- Floppy Kid Syndrome

- Hair loss in Angora Goats

- Icterus, Jaundice, 'Geelsig'

- Itching (Pruritic) Angora goats

- Lameness in Angora Goats

- Neurological Signs

- PHOTOSENSITIVITY in Angora goats

- Red Urine in Angora Goats

- Sudden death in Angora Goats

- 'Swelsiekte' - Swelling disease in Angora Goats

- SWELLING DISEASE (Swelsiekte) - Is this the answer?

- Swollen Joints

- SWOLLEN HEAD ‘DIKKOP’ IN ANGORA GOATS

- Diseases

- Abortion - Brucellosis melitensis

- Abortion - Enzootic abortion

- Abscess in Angora Goats

- ACIDOSIS

- Abscess – Foot Abscess ‘Sweerklou’

- Abscess - Trueperella pyogenes

- Abscess - Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis

- Anthrax (Miltsiekte)

- Bladder Stones

- Bloat in Angora Goats

- Bluetongue in Angora Goats?

- Botryomycosis – Pyogranulomatous bacterial infection in Angora goats

- Campylobacter

- Cancer- Heart (Sarcoma)

- Cancer - Jaw

- Cancer - Skin

- CCPP (Contagious Caprine Pleuropneumonia)

- Cerebral Gliosis and Spongiosis in Angora goats

- Clostridium Chauvoei - 'Sponsiekte’ Blackquarter

- Clostridiun Haemolyticum - Bacilliary Haemogloninuria ‘Red Water’

- Clostridium Novyi Type A - Dikkop Swelled Head

- Clostridium Novyi Type B – infectious necrotic hepatitis, black disease

- Clostridium perfringens Toxins

- Clostridium Perfringens Type A

- Clostridium Perfringens Type B

- Clostridium Perfringens Type C - Necrotic Enteritis

- Clostrdium Perfingens Type D

- Clostridium septicum - 'baarmoedersponssiekte'

- Cold (Hypothermia) and the Angora goat

- Cold - Why Angora Goats are More Susceptible in Summer than Winter

- Cretinism (Iodine Deficiency) In Angora Goat Kids

- Cryptosporidiosis in Angora Goats

- Diarrhoea in Angora Goats

- Domsiekte

- Draaisiekte

- Eperythrozoonosis (Mycoplasma ovis)

- Escherichia coli (E.coli)

- Fly Strike, Myiasis, ‘Brommers’

- Foot and Mouth Disease

- Footrot 'Vrotpootjie'

- 'Gallsickness' Anaplasmosis

- Graaff-Reinet disease - Maedi-Visna

- Hair loss in Angora Goats- Dermatophilosis

- Hair Loss in Angora Goats - Hypersensitivity Dermatitis

- Hair Obstruction (Trichobezoar) in an Angora goat kid

- Hairy Shaker Disease (Border disease)

- Heartwater

- Hypocortisolism in Angora Goats

- Johne's Disease

- Joint –ill (Angora Kids)

- Kid Mortality

- Leptospirosis

- Listeriosis

- Lymphocytic-Plasmacytic Enteris (LPE) IN ANGORA GOATS

- Mastitis 'Blue Udder' 'blou-uier'

- Meningoencephalitis (bacterial) in Angora goat kids

- Milk Fever, Parturient paresis

- 'Opthalmia' 'pink eye' 'aansteeklike blindheid'

- Polioencephalomalacia. Vit B1 deficiency

- Orf in Angora Goats

- Papillomavirus and Fibropapillomas in Angora goats

- Paralysis tick

- Pneumonia

- Peestersiekte

- Peste des petits (PPR)

- Phytobezoariasis (Plant hair balls)

- Pseudomonas infection in Angora goats

- Prolapse of Vagina, Rectum or Uterus

- Q-fever, Coxiella

- Rabies

- Rift Valley Disease

- Rhodococcus equi infection in Angora goats

- Salmonella

- Spring Lamb Paralysis

- Testicle Abnormalities in Angora Goats

- Tetanus

- Toxoplasmosis

- 'Twisted gut' 'Draaiderm' 'Rooiderm'

- Wesselsbron Disease

- Drugs

- Anthelmintic Drug Classification

- Anthelmintic Drug Lists update (Ontwurmmiddels)

- Anthelmintic Resistance

- Coccidiosis- Baycox and Vecoxan in weaned Angora kids

- Coccidiosis- off label treatments

- Combination Doses Better

- Dipping Guidelines - Ectoparasite Treatment

- Dipping Guidelines - Washing of Angora Goats

- Drugs for treating Coccidiosis in Angora Kids

- Ectoparasites Drug List

- EKO water trough tablets

- Fipronil, Abamectin (Atilla)

- Ivermectin Toxicity

- Levamizole Toxicity

- Lice Treatment

- Pain Relief Guidance

- Pain Relief Guidance- Off label drugs

- Pour-on Products Application to Alternative Sites

- Rafoxanide and Closantel Toxicity

- Field Studies

- Aloe Ferox

- Albumin: A predictor of survival rates in Angora goat kids

- Breeding worm resistant Angora's

- Coccidiosis- Baycox and Vecoxan in weaned Angora kids

- Coccidiosis- off label treatments

- Crypto - Screening for sub-clinical carriers

- Faecal egg and tick counts following treatment with Aloe Ferox

- Foot Abscess 'Sweerklou' Trial

- Lice Off-Label Treatment

- Lymphocytic-Plasmacytic Enteritis (LPE) in Angora Goats: Treatment - Field_Study

- Off-Label Coccidiosis Treatments- Angora goat kids

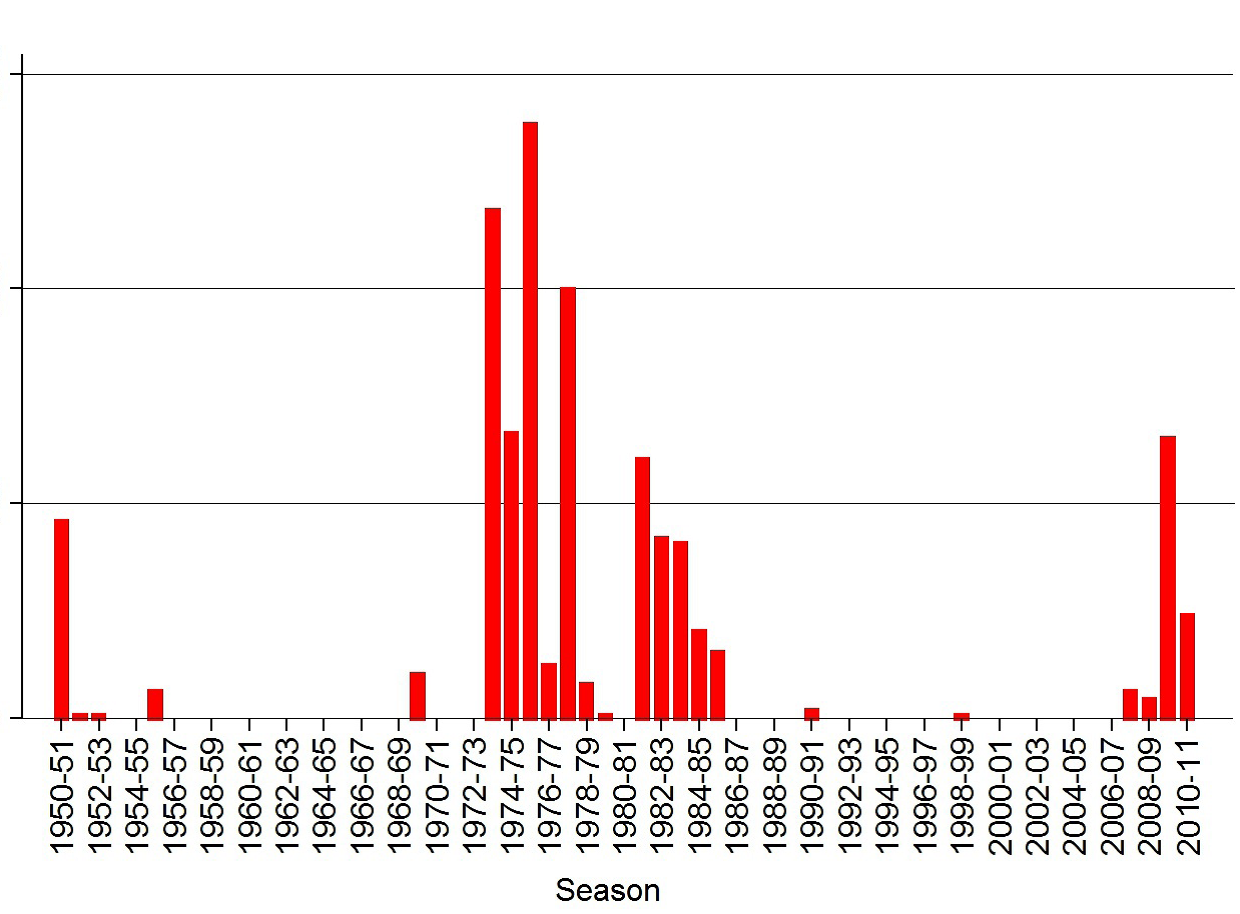

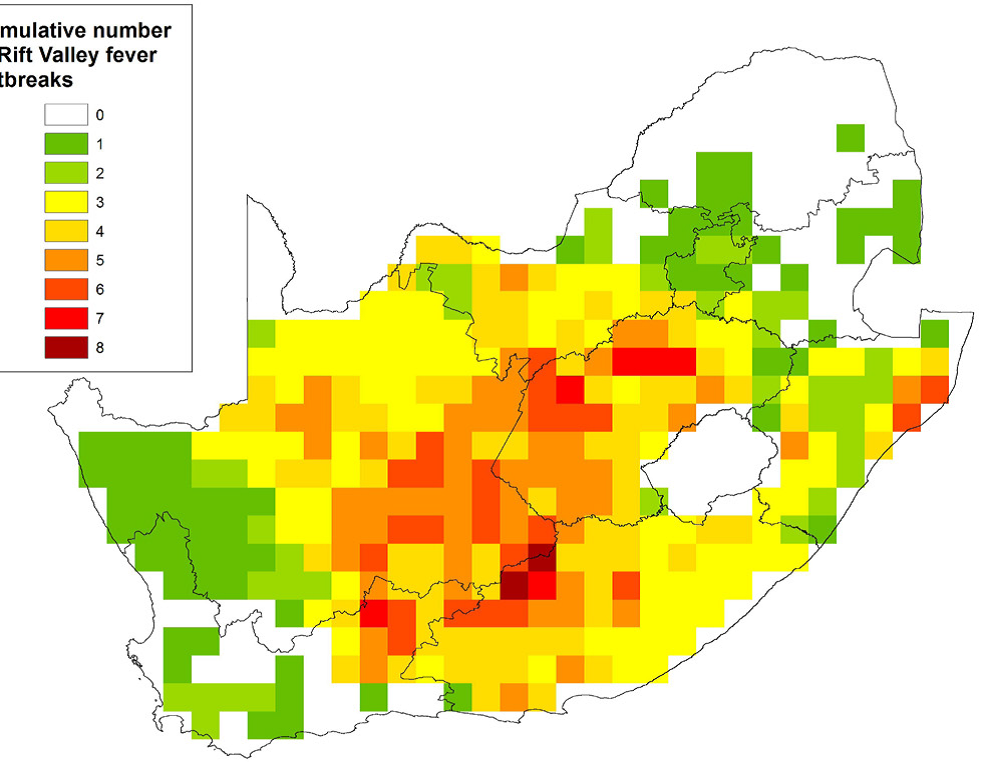

- Rift Valley Fever Seroconversion

- Rift Valley Fever (RVF) - Vaccinating maiden ewes each year

- Swelling Disease (Swelsiekte)

- Testicle Traits

- The Composition of Interstitial Fluid in Angora Goats

- The effect of Brevibacillus laterosporus (bioworx NEMAPRO) on internal parasites in Angora goats

- The impact of Brown Stomach worm (and Coccidiosis) on Angora Kids

- Treatment following Brown Stomach Worm and Cocidiosis infection

- Treatment of Lice, Ticks and Roundworms in Angora Goats

- Nutrition

- Amino Acid Requirements for Mohair Fibre

- Angora Goats on Lucerne

- BST use in Angora Goats

- Cobalt, Vit B12

- Copper Deficiency

- Copper Toxicity 'Geelsiekte'

- Drought Feeding

- Effect of Season on Mohair Fibre Diameter

- Effect on Mohair quality traits

- Feeding Ewes in Good Seasons - Is it Economical?

- Feeding Hansies

- Feeding weaned Angora kids

- Flush Feeding

- Goitre and Hypothyroidism (Iodine deficiency) in Angora goats

- Growth Rate of Angora Kids

- Hair Loss in Angora Goats - Nutritional Causes

- Importance of METHIONINE in Angora goats

- Licks Lekke

- Lucern Hay

- Maize/Mealies - Feed whole or finely ground?

- Maximising Production

- Milk production by the Angora Ewe

- Mineral analysis of the liver of goats

- Mineral and Vitamin Options

- PHOSPHORUS (P) Deficiency

- Polioencephalomalacia. Vit B1 deficiency

- Pregnant and Lactating Ewe

- PROTEIN what do the terms mean?

- Salt in Angora Goats

- Selenium Supplementation

- The Effect on Mohair Production

- The importance of Fibre when feeding Angora goats

- Urea Poisoning

- VITAMIN AND MINERAL SUPPLEMENTS REQUIREMENTS FOR ANGORA GOATS

- Weaning and the First 18 Months

- Whats in a bag of feeds?

- When should we feed Angora ewes?

- When to Give Supplementary Feed

- White Muscle Disease in Angora Goats

- ZINC Deficiency

- Parasites

- Angora Goats have Paler Mucous Membranes

- Brandsiekte

- Breeding worm resistant Angora's

- Brown Stomach Worm

- Coccidiosis

- Conical Fluke

- Diatomaceous Earth as an alternative treatment for internal parasites

- EKO water trough tablets

- Faecal Egg Count (FEC)

- Hair Loss in Angora Goats - External Parasites

- Immunity in Angora goats

- Lungworm in Angora goats

- Lice and Angora Goats

- Liver Fluke in Angora Goats

- Nasal Worm

- Roundworm Management Strategies

- Targeted Selective Treatment (TST)

- Tape Worm

- The impact of Brown Stomach worm (and Coccidiosis) on Angora Kids

- Ticks

- Warble Fly

- Wireworm/Haarwurm

- 'Uitpeuloog' Gedoelstia

- Poisoning

- Asbos - Mesembryantheium

- Aflatoxicosis

- American Aloe (Agave americana) 'Garingboom'

- Asaemia axillaris – ‘Vuursiektebossie’

- Botulism 'Lamsiekte'

- Copper Toxicity 'Geelsiekte'

- Cynanchum spp (bobbejaantou)

- Datura (Stinkblaar) poisoning in Angora Kids

- Dikoor: Panicum spp- Buffalo grass

- Diplodia maydis (Diplodiosis) - Harvested maize

- 'Geeldikkop' Tribulus terrestris

- GANSKWEEK

- Lonophore Poisoning

- Ivermectin Toxicity

- 'Kaalsiekte' 'Lakteersiekte'

- Mesembryanthemum and Opuntia Spp (Vygies and Turksvry)

- Mexican Poppy- Argemone Mexicana

- Nitrate Poisoning

- Krimpsiekte (Cardiac Glycosides)

- ‘Kweek Tremors’, Cynodum dactylon

- Levamizole Toxicity

- Melia azedarach (Syringa berry)

- 'MELKBOS' Euphorbia mauritanica

- 'MELKTOU' Sarcostemma viminale

- mycotoxins

- Nenta, Plakkies, Pigs ears - Kalanchoe, Cotyledon spp

- Organophosphate containing dip

- Pithomyces chartarum- ‘Stellenbosch photosensitivity

- Prussic acid Poisoning 'Geilsiekte'

- Pteronia pallens- witbossie, Scholtz-bossie

- Rafoxanide and Closantel Toxicity

- Salt Poisoning

- SATANSBOS, Silver-leaf nightshade.

- Slangkop - Drimia spp

- ‘Springbokbossie’ ‘Malkopharpuis’ Hertia pallens

- Tulp - Morea spp

- Urea Poisoning

- Vermeersiekte

- Waterpens

- 'WITSTORM' 'VAALSTORM' Thesium spp.

- Reproduction

- Artificial Insemination

- Breeding a Hardy Angora Goat

- Dystocia - Difficult Births

- Ewe AgeEffect on Reproduction

- Ewe Selection

- GENOMICS- Genetic selection potential (parasites, disease and production parameters)

- Impact of Shearing on Reproduction

- Kid Mortality

- Lamhokke

- Managing the pregnant ewe

- Mating on Lucerne lands

- Mineral and Vitamin supplementation effect on reproduction in Angora goats

- Oestrus and Mating in Angora Goats

- Out of Season Breeding in Angora goats

- Paraphimosis of the penis

- Performance Testing - Angora goat breeding

- Pigment in Angora goats

- Rams per Ewe Ratio

- REPEATABILITY and HERITIBILITY traits

- Selection for Body Weight in Angora Kids and Young Goats

- Semen Freezing And Subsequent Insemination In Angora Goats

- Synchronisation Program for Angora Goats

- Teaser Rams

- Testicle Traits

- The Weak and Cold (Hypothermic) Angora Kid

- Testicle Abnormalities in Angora Goats

- Vaginal Prolapse

- Weaning shock in Angora goat kids

- Weaning - The Angora goat ewe

- Weaning the Angora Goat Kid

- Vaccines

- Anthrax Vaccination in Angora Goats

- Clostridium and Pasteurella Vaccine (update)

- Orf, Scabby Mouth, ‘Vuilbek’ Vaccination

- Pasteurella Vaccines

- Rift Valley Fever Seroconversion

- Rift Valley Fever (RVF) - Vaccinating Maiden Ewes Each Year

- Vaccine Handling

- When to Vaccinate

- What vaccine cover do Angora goats need?

- Bio Security

- Procedures and Protocols

- Angora Goat First Aid

- Animal Identification - Tattooing

- Body Condition Score

- CAESARIAN by Veterinarian

- Castration - Burdizzo

- Euthanasia Protocols

- Faecal Egg Count - How to do

- Fire Burn Wounds in Angora Goats

- Handling Angora Goats

- Health Check on Angora Goats

- Hoof Care

- Horn Trimming

- How to conduct a basic Post Mortem on an Angora Goat

- How to dose an Angora goat

- How to perform a castration on Angora Goat

- Injecting Angora goats

- Lancing an-Abscess

- Mohair Disease Surveillance

- Paraphimosis of the penis

- Plunge Dipping

- Shearing Guidelines

- Shearing Wounds

- Stomach Tube

- Stress in Angora Goats

- Transporting Angora goats